Systemic Sexism: Struggle

15 Dec 2025

In the last article, we talked about history: where traditional gender norms come from, and how they were made by men to favour men. But sexism isn’t a past issue: it’s a living one, exactly because these norms are still being handed down from generation to generation in the name of tradition. It’s time to zoom in on how these norms actually affect people day by day in our current society.

Gender norms aren’t just traits associated with being a man or a woman. They represent how men and women are expected to behave, and what makes them worthy or not worthy of respect. So what do traditional gender norms value in a woman? What do traditional gender norms say about how a woman has to behave? It centres around two concepts. These are her sexual attractiveness and her sexual non-promiscuity- or ‘chastity’, to use an older word. In other words, a woman is judged by her capacity to be an exclusive sexual possession for men: the exact situation you’d expect if the norms for being a woman were devised by men.

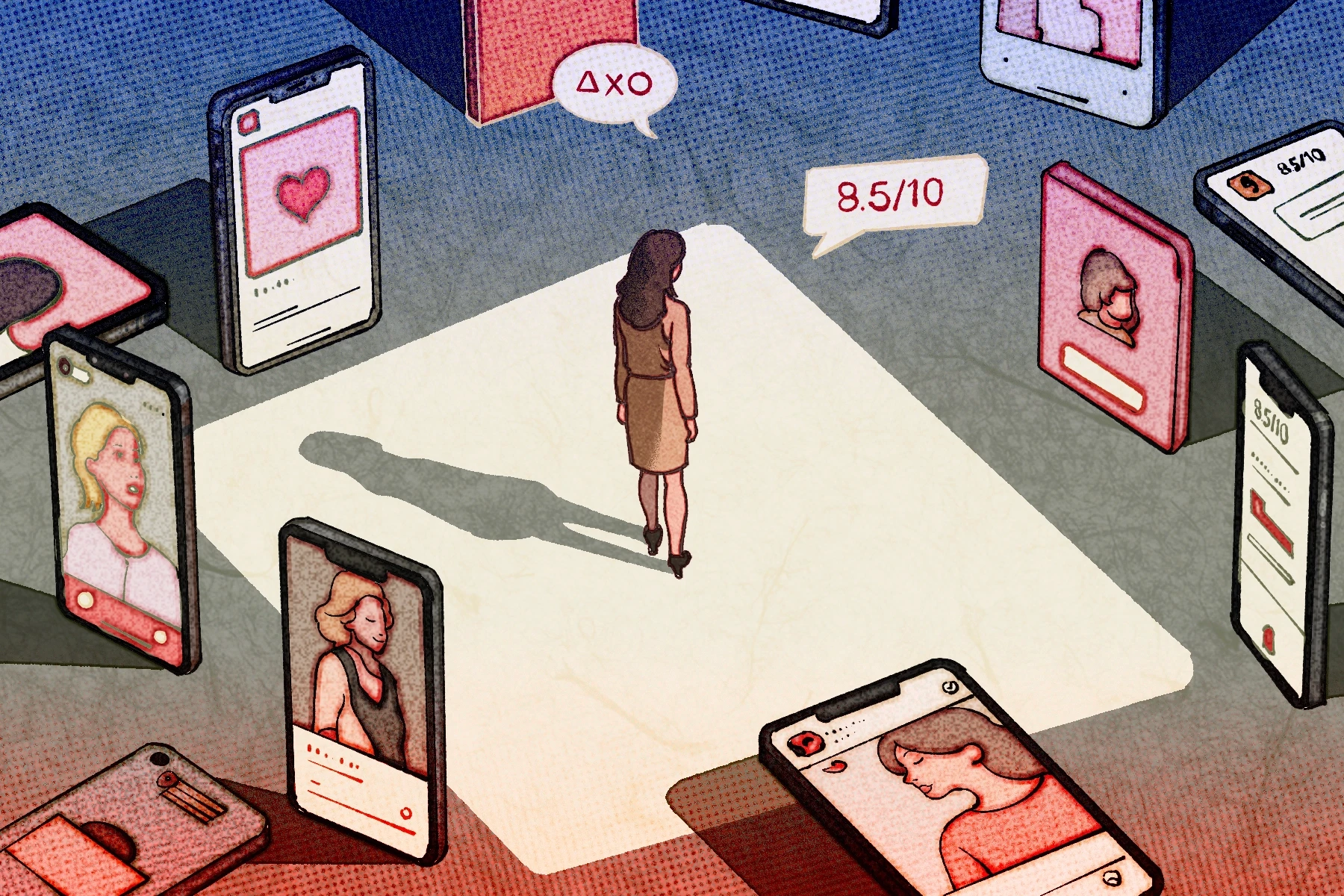

This may sound strange, but once you become aware of it you see examples of it everywhere. Take the massive societal obsession with female attractiveness. In loads of films, especially older ones, the female characters aren’t expected to be witty or cool or useful to the plot- they’re only there to look pretty. The harshest insult for a woman is calling her ugly or fat; when women receive hate comments online these invariably focus on her appearance; and women continually get complimented not on the basis of who they are as people but by being ‘eye-candy’ or ‘nice to look at’. Just look at how women get reduced to a rating scale based on how good-looking they are, described not as a human being but as a number. There’s mountains of scientific evidence for how all this pressure to look good bears down on women and affects their mental health; and how that’s knowingly exacerbated by social media.

Men, of course, also feel pressure to be attractive. But the magnitude of that pressure is different because their value isn’t computed in that way; their attractiveness doesn’t define who they are. Men are pressured to be tall and strong: but even if they’re not, they will still receive a basic minimum of respect. They will still be listened to in conversation, people won’t talk over them as if they weren’t even speaking, and their basic autonomy will still be upheld. You can find out for yourself how this plays out in real life. Ask a female friend or relative how many times they’ve been sitting in a group and a man has joined the conversation saying hi to only the men and to the women he finds pretty there. Ask them how differently men treat them and their friends based on whether they find them attractive or not: seeing the reality of how systemic sexism works really is this easy.

In short, men considered unattractive will still be treated as people. Women considered unattractive may not: so the need to be sexually appealing is massive, and the beauty industry is worth billions. Aging, already a potential source of stress for men, becomes a source of terror for women, because the gradual loss of a youthful appearance represents the gradual loss of being treated like a person.

What about ‘chastity’? Think about how omnipresent slut-shaming is, or how male rappers and influencers classically distinguish between ‘good girls’ and ‘hoes’. Think of how promiscuous women are constantly referred to not as people but as ‘thots’, ‘sluts’, ‘whores’, and worse. When you start to reduce a human being to being a slut or a 5, when a person becomes a number or an insult used to devalue them- that’s dehumanisation.

‘Dehumanisation’ may sound exaggerated, but you don’t have to take my word for it. This isn’t a melodramatic opinion: there’s a huge amount of scientific evidence that this is genuinely what happens, and it has extremely unjust consequences. For example, even rape victims who dress ‘immodestly’ are blamed for their own victimisation due to their implied promiscuity. To make the recognition of severe trauma dependent on controlling what someone wears is precisely what dehumanisation is.

For a woman to be described as a ‘good girl’, she is expected to stay confined at home, not going out- although for men, going out and actually enjoying life is always OK. She’s meant to make herself look nice for the men in her life, and do what they say. In other words, she’s not meant to be a person, but a prop. No wonder men use femininity itself as an insult, using words like ‘pussy or ‘bitch’ to degrade each other: because traditional norms of femininity are degrading.

So within the framework of traditional gender norms, husbands may still love their wives and a man may still care for a woman, but this is contingent on the woman’s ‘ladylike’ acquiescence to the norms which devalue her anyway.

Women then become socialised into judging themselves and others on their capacity to play this role of sexual possession- being attractive, not having sex (although men having frequent sex is of course celebrated), and obeying men- because it’s a survival strategy to limit their dehumanisation. The classic example of this is women slut-shaming women: an example of norms being drilled into a victimised group, whereupon they are made to perpetrate their own victimisation by turning on each other.

But although women can try to be ‘good’ and limit their complete dehumanisation, in a unjust system they can indeed only ever limit it. No matter how much women play by the unfair rules, they can still get victimised anyway. Ask your sisters, mums, aunts, grandmas, cousins, and female friends whether they’ve ever been groped. Ask your parents how downplayed and normalised groping was until very recently: think of how late the #MeToo movement emerged and how bitterly contested it is now. When a man gropes a woman, he is claiming a kind of ownership over their body, the right to use it for his benefit without consent. It is not ‘just a bit of fun’- it is the theft of a woman’s sovereignty over her own body.

But it’s more than that: it’s the casual assumption that the purpose of a woman’s body is male gratification. Women existing as a means to an end for men is, in fact, deeply normalised. Think of how many men in songs, raps, and your friend groups brag about ‘getting’ (i.e. manipulating) women to sleep with them and then cutting contact after. Using somebody as a thing- rather than treating them as a person- is plain dehumanisation, but being a ‘heartbreaker’ is still seen as virility instead of sociopathy.

And this isn’t taken seriously because, as your female friends and relatives will tell you, women themselves often aren’t taken seriously. Even violence against them often isn’t taken seriously: think of how often you hear that ‘boys will be boys’ in excuse for groping (sexual assault), or that rape victims are ‘asking for it’ and ‘should bear some responsibility’.

The daily struggle to win respect, the constant fear of being assaulted, and the repeated experience of being used as an object: all this manifests as an immense psychological toll which men often find difficult to understand. But you don’t need to take my word for it: the best way to understand how men’s and women’s daily lives are so different is to just ask a woman yourself.

Ask any woman in your life about how often they’ve been followed home; or actually chased home and had to sprint away from some stranger; had strangers stare down their top; been called names in public. Ask them about not being able to relax on a night out because there’s an omnipresent risk of being harassed or groped or worse; having to constantly be vigilant walking down the street because at any moment somebody might take advantage of you; having your loved ones and friends dismiss all this as you ‘overthinking it’.

In fact, it’s not just in people’s heads: it’s verified by statistical evidence. Studies continually validate the massive disparity in stress between men and women. Studies also validate that this cannot be dismissed as just hormones or biology.

Because all these different ways in which women get treated add up. It means that women are living a fundamentally different kind of life to men in our society, not because they’re ‘hormonal’ or ‘emotional’, but because their society thinks that’s OK.

————————————————

words & glorious research by Daniel Aaron Levy creator of Polymath

art by Feimo Zhu (Instagram & LinkedIn)

References & Further Reading

Frederickson BL, Roberts TA. Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women's Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21(2).

Perloff RM. Social Media Effects on Young Women’s Body Image Concerns: Theoretical Perspectives and an Agenda for Research. Sex Roles. 2014;71:363-377.

Wells G, Horwitz J, Seetharaman D. Facebook Knows Instagram Is Toxic for Teen Girls, Company Documents Show. September 14, 2021. Available at: HYPERLINK "https://www.wsj.com/tech/personal-tech/facebook-knows-instagram-is-toxic-for-teen-girls-company-documents-show-11631620739" https://www.wsj.com/tech/personal-tech/facebook-knows-instagram-is-toxic-for-teen-girls-company-documents-show-11631620739 . Accessed July 18, 2025.

Kumar N. Beauty Industry Statistics 2025 (Cosmetic Market Size). July 4, 2025. Available at: HYPERLINK "https://www.demandsage.com/beauty-industry-statistics/" https://www.demandsage.com/beauty-industry-statistics/ . Accessed July 18, 2025.

Heflick NA, Goldenberg JL. Objectifying Sarah Palin: Evidence that objectification causes women to be perceived as less competent and less fully human. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(3):598-601.

Loughnan S, Pina A, Vasquez EA, Puvia E. Sexual Objectification Increases Rape Victim Blame and Decreases Perceived Suffering. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2013;37(4):455-461.

Nussbaum MC. Objectification. Philosophy & Public Affairs. 1995;24(4):249.

Mayor E. Gender roles and traits in stress and health. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:779.

Watson LB, Marszalek JM, Dispenza F, Davids CM. Understanding the Relationships Among White and African American Women’s Sexual Objectification Experiences, Physical Safety Anxiety, and Psychological Distress. Sex Roles. 2015;72:91-104.

Young Women's Trust. Impact of sexism on young women’s mental health. November 17, 2019. Available at: HYPERLINK "https://www.youngwomenstrust.org/our-research/impact-sexism-young-womens-mental-health/" https://www.youngwomenstrust.org/our-research/impact-sexism-young-womens-mental-health/ . Accessed July 18, 2025.

Kelly MM, Tyrka AR, Anderson GM, Price LH, Carpenter LL. Sex differences in emotional and physiological responses to the Trier Social Stress Test. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2007;39(1):87-98.