Systemic sexism: History

2 Dec 2025

What is it like to be a woman?

Of course, as a man, that’s not something I can properly answer. But systemic sexism isn’t just an assertion, or a theory: it’s a scientifically proven issue which affects the whole of society. And as a member of that society, it’s important to understand it. A good starting point for doing so is, fittingly, with a scientific study.

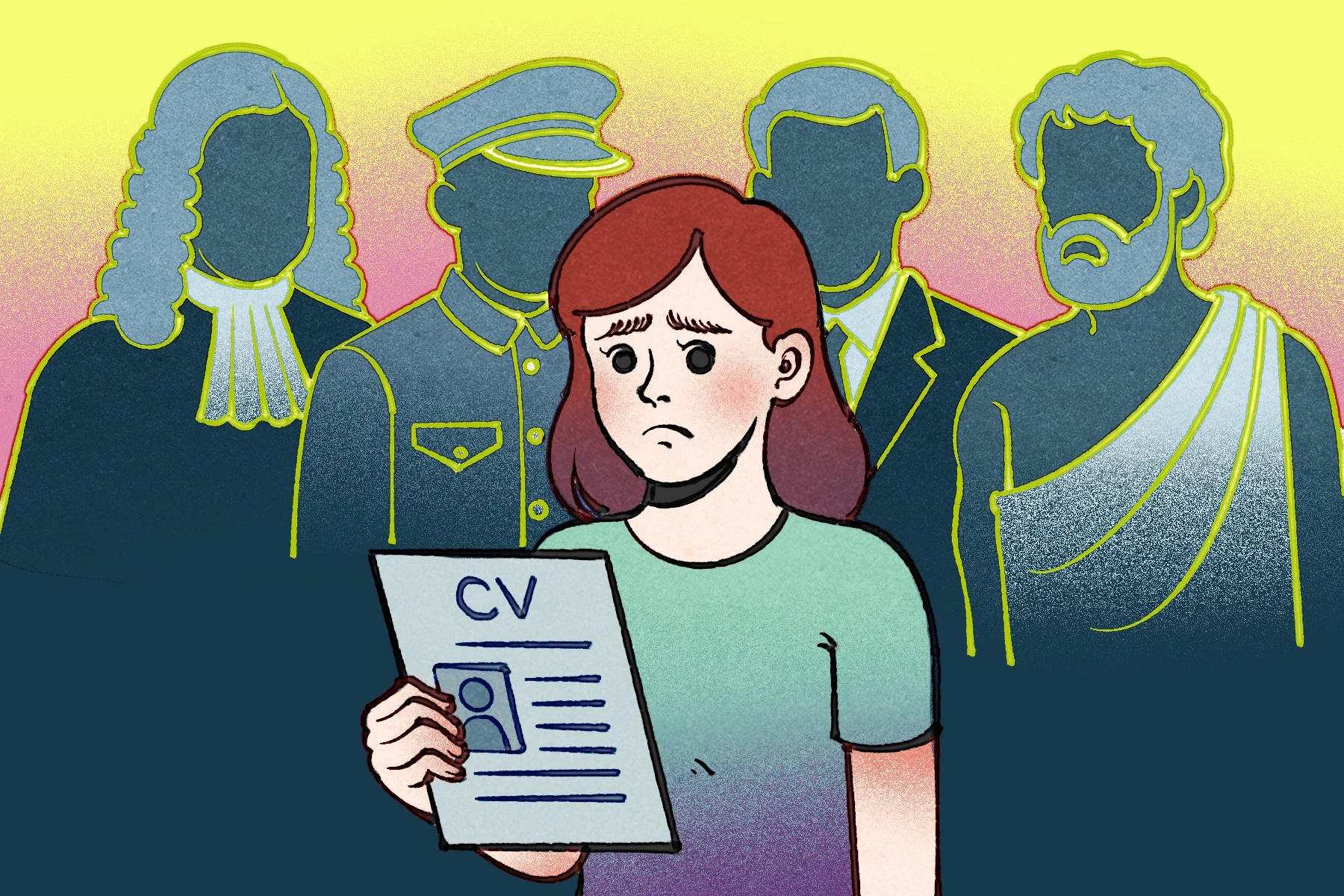

In 2012, 127 U.S. university staff were given a fake student’s CV and asked to evaluate it. The CV was always the exact same- except for one difference. Sometimes it had a man’s name, and sometimes it had a woman’s name. When it had a woman’s name, staff rated the student as being less competent, were less likely to hire them, and would start them on a lower salary. But many of these university staffers were themselves women. It’s unlikely that highly-educated, often liberal-leaning, American women were knowingly biased against female candidates. So what happened?

In reality, just because we’re not consciously aware of how we judge people differently, that doesn’t mean we don’t do it. In fact, 95% of our thinking isn’t conscious at all. One of the biggest misconceptions about human nature is that we’re rational machines which compute our beliefs independently of everyone else: we don’t. In reality, our beliefs are shaped by a massive subconscious world of biases, associations, expected behaviours, and values. We absorb all of these from the society around us as we grow up- our parents, our schools, our culture, from TV shows, films, and other media, and more- without even realising it. We then assume that the way we think about, for example, what it means to be a man or a woman is somehow totally independent of this whole environment; and we don’t stop to question where our beliefs are come from and how we even came to believe them. In sociology, these absorbed phenomena are called ‘normatives’, or ‘social norms’7- and understanding these is key.

Being a man or a woman isn’t just about chromosomes, because we don’t live in a biology textbook. Real societies attach an intricate web of norms to each gender- which sounds a bit abstract, but is instantly recognisable in our everyday experience. Different genders are associated with things like the clothes that people wear, the media (TV, films, songs, etc) they consume, the slang they use. Even different colours (e.g. pink and blue) and drinks are associated with different genders, not to mention haircuts and stereotypical personality traits. When people say ‘gender is a social construct’, they’re not ignoring the biological reality of chromosomes. They’re just making the logical distinction between that biology (what scientists call ‘sex’) and the collective packages of norms seen in a society: this is gender. It’s sociological, not biological. It’s real life.

So where does this massive web of gender norms- that we absorb without even realising it- come from?

As with all ‘traditional’ norms, they come from history.

When we think of history, most of us already know that in the past almost all the leaders were men. But it’s deeper than that: all the bureaucrats, the generals, the MPs, the judges, the businessmen, the scholars, the writers, the philosophers throughout history have all almost universally been men. Right from the genesis of civilisation in the 4th millennium BCE until very, very recently.

For almost all that stretch of time, education itself was historically limited to men. For the masses, literacy was limited to men. Women’s designated social role was not to participate in society, but to isolate themselves strictly at home, passively accepting the authority of males. So whilst societies establish their own norms, participation in these societies was limited to men, and men had the ability to establish whatever gender norms they desired.

It is one of the most basic principles of both social science and common sense that groups given unchecked power abuse it. History is an unbroken record of this fundamental truth: think of all the absolute monarchies, feudal systems, castes, and dictatorships. So when men had exclusive control over societal norms, those norms were (unsurprisingly) shaped to glorify male dominance and enforce female subordination.

What does this actually mean in practice? It means that under traditional gender norms, being a man is stereotypically associated with being rational, independent, assertive, competent, and intellectual. This comes at the expense of being a woman, which is stereotypically associated with being emotional, irrational, dependent, submissive, and ‘hormonal’.

But being ‘emotional’ isn’t gender-specific: human beings have emotions. However, when men get angry, it’s not conceptualised as being ‘emotional’ or ‘hormonal’- but as being manly. In other words, emotions in women are used to discredit them, whereas emotions in men are used to glorify them. All the stereotypes of women are being less intelligent, rational, or capable than men are bluntly disproved by the actual scientific evidence. The norms don’t check out. But traditional norms are never based on evidence, or science: they’re only based on tradition.

And these traditional norms- from thousands of years ago when neither human rights nor electricity were even conceivable- have stayed with us. They’ve been passed down from generation to generation exactly because we unconsciously absorb the beliefs that are around us. Hence in that 2012 study, even women wanted to hire women less. It’s not just economic concerns about pregnancy and maternity leave: they were rated as being genuinely less competent despite the CV being the exact same. And all of this matters so much because if women are ‘homemakers’ without employment, they’re totally dependent on male ‘breadwinners’ for their existence; which makes them vulnerable to abuse.

Femaleness, of course, is also traditionally associated with the positive qualities of being ‘nurturing’ and ‘empathetic’. But by assigning these traits to the ‘second sex’ it simply liberates men from having to abide by them. To raise half a society on the idea that they must be dominant- but are not expected to be good- has profound human consequences.

And the anthropological evidence here is clear: none of these traditional gender norms are due to any innate gender differences in physical strength or biology. Human beings evolved to live as small bands of hunter-gatherers, and these are famous for their attitudes of gender equality. Traditional gender norms don’t come from human nature: they come from societies, in contexts both within and outside the West- in other words, across the world.

For much of Ancient Roman history, for example, the rape of a woman was not a crime against her, but to the male head of her family: for property damage. The rights and feelings of the woman were irrelevant. The Romans also approved of wartime rape: for establishing Roman dominance over other nations.

Obviously, we’re not in Ancient Rome anymore. But traditional gender norms in the West have still evolved from this historical context, and the themes of ownership and dominance are still there. Domestic abuse and marital rape were only made illegal in the West in the late 1900s. In many non-Western societies, they’re still completely legal and culturally acceptable. We are still standing in history’s shadow.

————————————————

words & glorious research by Daniel Aaron Levy, follow their YouTube: Polymath

art by Feimo Zhu (Instagram & LinkedIn)

References & Further Reading

Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J. Science faculty's subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(41):16474-16479.

Young E. Lifting the lid on the unconscious. New Scientist. July 25, 2018. Available at: https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg23931880-400-lifting-the-lid-on-the-unconscious/. Accessed October 7, 2025.

Wilson T. Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious. Cambridge & London: Belknap Press; 2002.

Geertz C. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York City: Basic Books; 1973.

DiMaggio P. Culture and Cognition. Annual Review of Sociology. 1997;23:263-287.

Bandura A, Walters RH. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice hall; 1977.

Berger PL, Luckmann T. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. London: Penguin Books; 1991.

World Health Organization. Gender and health. May 24, 2021. Available at: HYPERLINK "https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/gender-and-health" https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/gender-and-health . Accessed July 18, 2025.

Phillips SP. Defining and measuring gender: A social determinant of health whose time has come. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2005;12:4-11.12.

Hyde JS. The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist. 2005;60(6):581-592.

de Beauvoir S. The Second Sex. New York City: Random House; 1997.

Lerner G. The Creation of Patriarchy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1986.Kelly RL. The Foraging Spectrum: Diversity in Hunter-Gatherer Lifeways. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press; 1995.

Kelly RL. The Foraging Spectrum: Diversity in Hunter-Gatherer Lifeways. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press; 1995.

Ortner S. Is female to male as nature is to culture? Woman, Culture, and Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1974.